The Indian Space Research Organisation's (ISRO's) Chandrayaan 2 orbiter has got its first taste of a solar flare — an important requirement for the spacecraft to study what the Moon's surface is made up of. Essentially, high energy radiation from the Sun helps "illuminate" the lunar surface, allowing the orbiter's instruments to gather additional data on the composition of the Moon's surface elements. ISRO has shared data that the orbiter's Solar X-ray Monitor collected on the flare.

The Sun's surface and its atmosphere are violent places. It isn't just the heat and pressure that will get you — these places also release periodic, powerful explosions jetting out from the Sun's surface. Each of these explosions is also timed with surges in harmful ultraviolet (UV) radiation and X-rays. Like clockwork, these intense fluctuations vary in an eleven-year cycle — oscillating between a very evident solar "maxima" and "minima" in that time.

The volume of X-ray emissions each year vary depending on the stage of the solar cycle. But evidently, there are also episodes when solar X-rays show large variations over a much shorter span of time — minutes or hours. These are dubbed 'solar flares'.

The Solar Dynamics Observatory, a NASA organisation, observed a medium-sized flare that lasted almost 2 hours, and a coronal mass ejection erupting from the same, large active region on 14 July 2017. Image: NASA

The Orbiter's instruments are sensitive to the diversity of elements in the lunar soil. ISRO clarified that one of the orbiter's important goals — mapping the elements and minerals that make up the lunar soil covering the Moon, was best done when a solar flare was in progress. There are two instruments on Chandrayaan 2 that are key to this study: the Large Area Soft X-ray Spectrometer (CLASS) and the Solar X-ray Monitor (XSM).

'Flash photography' to illuminate elements

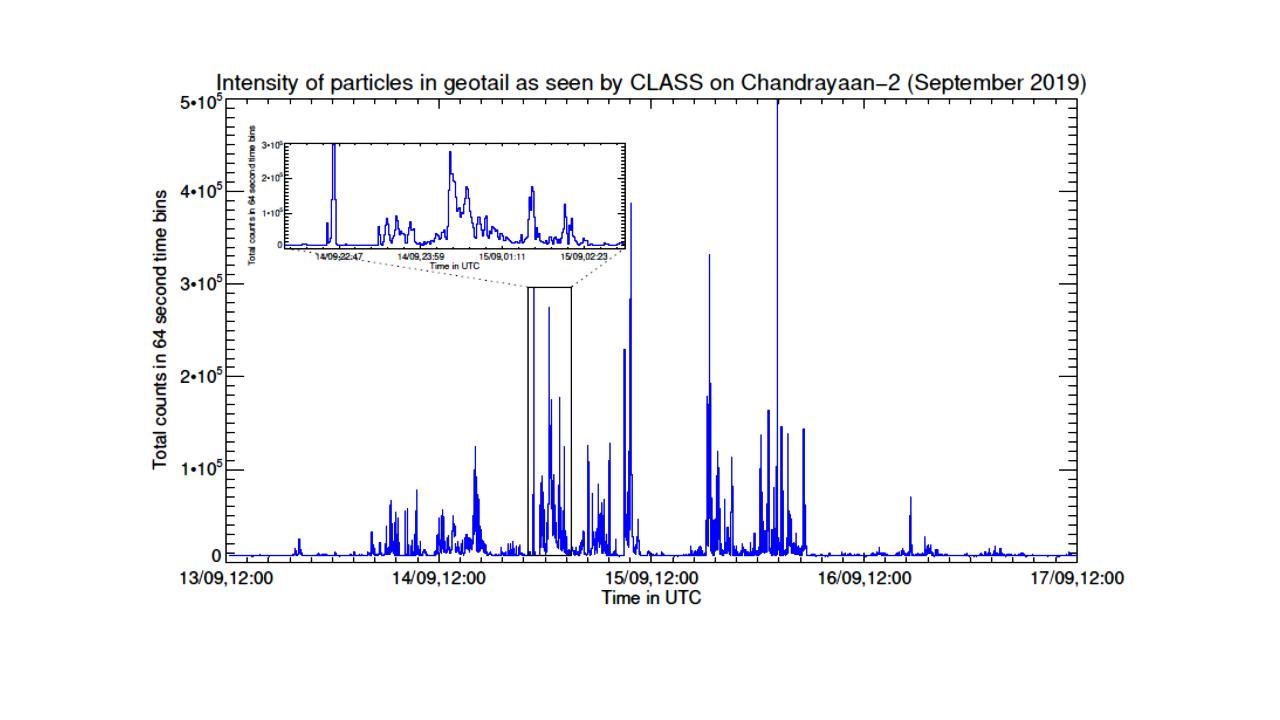

The CLASS instrument on Chandrayaan 2 is designed to pick up signatures of elements in the lunar soil. These signatures are observed very well when solar flares on the Sun send X-rays sweeping across the solar system. Being a rich source of X-rays, solar flares illuminate the Moon's surface as they strike it. This prompts the elements to absorb these X-rays and emit a unique spectrum of light basis which element it is. These "secondary X-ray emissions" can be read by Chandrayaan 2's CLASS instrument to produce a graph that looks something like this:

Data from the CLASS instrument on Chandrayaan 2 shows the intensity of particles in the Earth's geotail, September 2019. Image: ISRO

This "flash photography" technique used by the orbiter needs prior planning to coincide with events dictated by the Sun. ISRO said that more observations in Chandrayaan 2's future and from other space missions can help unravel the "dance of electrons to the music of magnetic fields" happening around the Moon.

Solar wind and the Earth's geotail

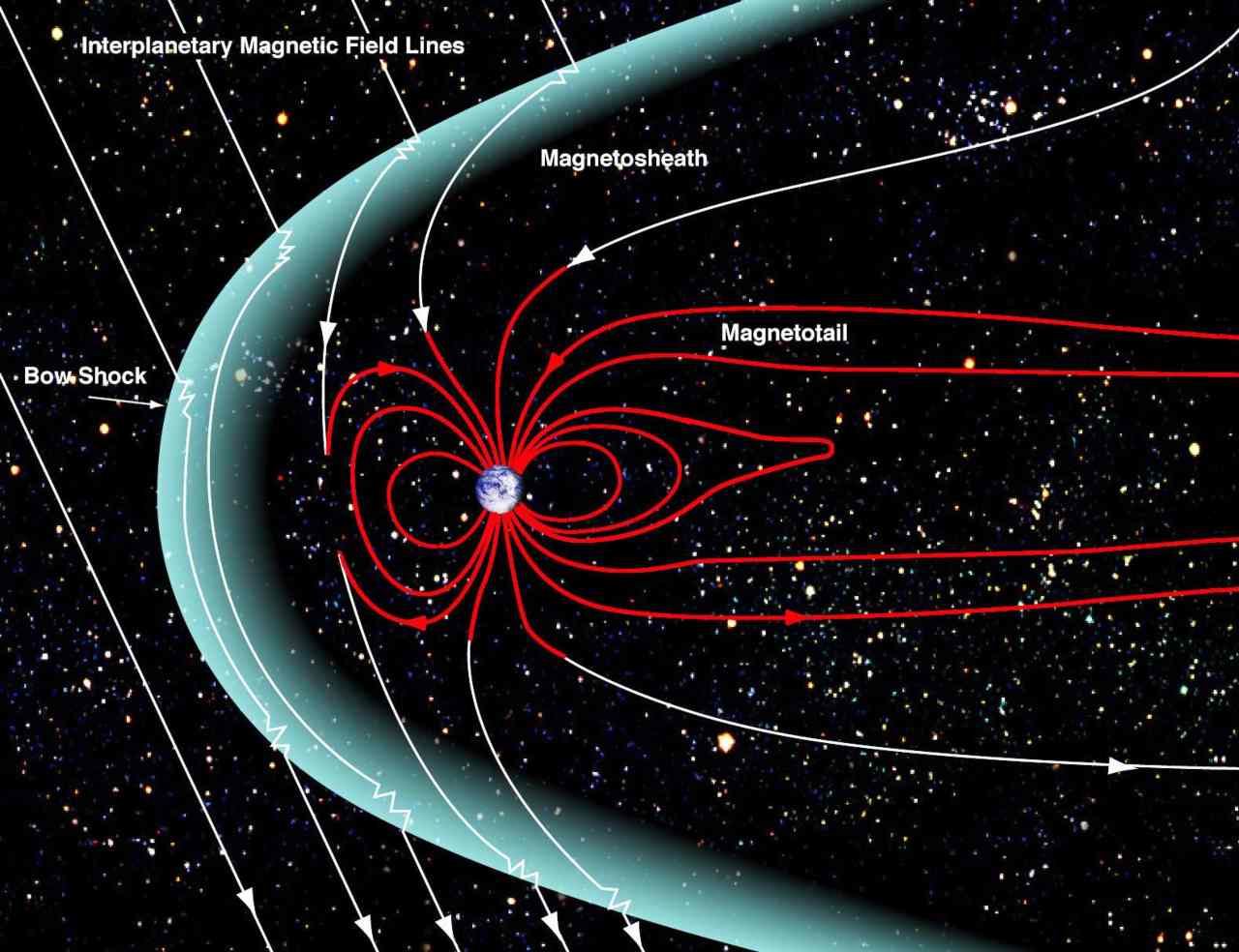

For ISRO, solar wind episodes also present an opportunity. The Sun's plasma, which comprises charged particles embedded in the far-reaching magnetic field of the Sun, moves at whopping speeds of a few hundred kms per second. Along the way, this plasma interacts with planets and space rocks — the Earth and Moon included. Thankfully, we Earthlings are spared from the wrath of solar wind by the Earth's own, fairly powerful magnetic field, which deflects charged particles with ease. This interaction creates a magnetic envelope around Earth, much like a shield, called the magnetosphere.

Earth's magnetosphere isn't an even layer enveloping the planet like the atmosphere is — it is three to four times the Earth's radius (extending ~22,000 km from the surface) on the side of the planet facing the Sun. This also creates a long tail (similar to a comet's tail) on the opposite side, which is long enough to extend past the Moon's orbit.

Every 29 days, the Moon experiences six days (often accompanied by a Full Moon) under the geotail's influence. ISRO has also timed the orbits of the Chandrayaan 2 orbiter so it can cross this geotail and study how it behaves hundreds of thousands of kilometers from the Earth. This is the first scientific data collected by the Chandrayaan 2 mission. Earlier this week, ISRO released the first high-resolution images of the Moon's surface features and the first scientific data from the Chandrayaan 2 mission.

Captured by the Orbiter's High-Resolution Camera (OHRC) from an altitude of ~100 kilometres, ISRO shared that the images are the highest resolution visuals ever taken of the Moon.

Closeup images of the Moon's surface captured by the Chandrayaan 2 Orbiter's High-Res Camera (OHRC). Image: ISRO

Closeup of boulders on the Moon's surface, captured by the Chandrayaan 2 Orbiter's High-Res Camera (OHRC). Image: ISRO