Google’s Android, now 10 years old, has not been a stranger to security issues over the years. But with the mobile operating system now installed on over 2 billion devices globally, Google has been taking an increasingly firmer grip on trying to bring the problem under control. Now, the company has published its lengthy annual update to take stock on just how well that is going.

It’s a slippery slope to be sure, with the number of apps and the enterprising attempts to maliciously exploit them both growing. To wit, 0.04 percent of all downloads from Google Play were classified as potentially harmful applications (PHAs) by Google, versus 0.02 percent in 2017 — an increase in part because Google is growing the categories it’s identified and is tracking.

But Google said that new policies, such as more privacy-hardened APIs, along a wider implementation of Google Play Protect — its built-in malware scanner that comes with unforked versions of Android — have contributed to the company overall making a dent in the problem.

One area that Google singled out in the report this year was the impact that it’s having on protecting devices and users when they download and use apps from outside the Google Play store.

As this is a newer area that it’s tackling with more focus, there are more quantifiable wins to be had, and broadcasted. It didn’t provide a specific figure for how many PHAs it blocked from the Google Play store in 2018 (note that in 2017 it did disclose this: it was 700,000). But in 2018 it noted that “Google Play Protect prevented 1.6 billion PHA installation attempts from outside of Google Play.”

Notably, when it comes to apps on the Google Play store, on devices running unforked versions of Android, the dent seems to be mostly keeping the problem of potentially harmful applications at bay, while the impact on apps that are sideloaded not through Google Play has been more pronounced.

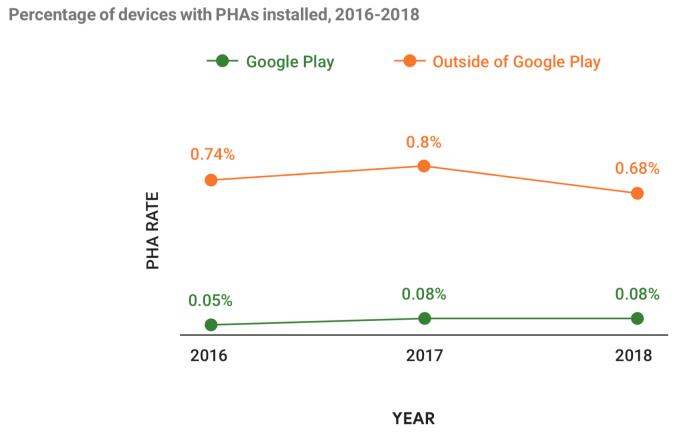

Google noted that in 2018, some 0.08 percent of devices that used Google Play exclusively for app downloads were affected by PHAs. That figure, however, is actually the same as the year before, and actually a bit higher than the year before that.

In contrast, the impact on those downloaded outside of Google Play has been more dramatic — albeit the problem is clearly a bigger one. The number detected in 2018 stood at 0.68 percent, down 15 percent from 0.8 percent a year ago (which itself also had gone up from 2016).

The chances of installing malicious apps, meanwhile, are improved if you have Google Play Protect working. Some 0.45 percent of Android devices using it, installed PHAs, down from 0.56 percent in 2017.

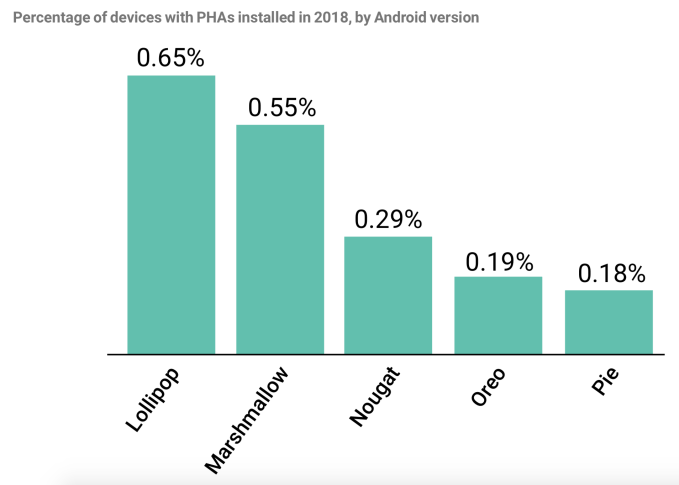

It seems also that this trend is partly down to general improvements over time across the whole Android ecosystem, with later versions of the OS showing better rates of PHA installs. Notably, however, the reduct between Oreo and Pie was only a 0.01 percentage point. It’s getting more challenging to address the problem after more drastic reductions in earlier years.

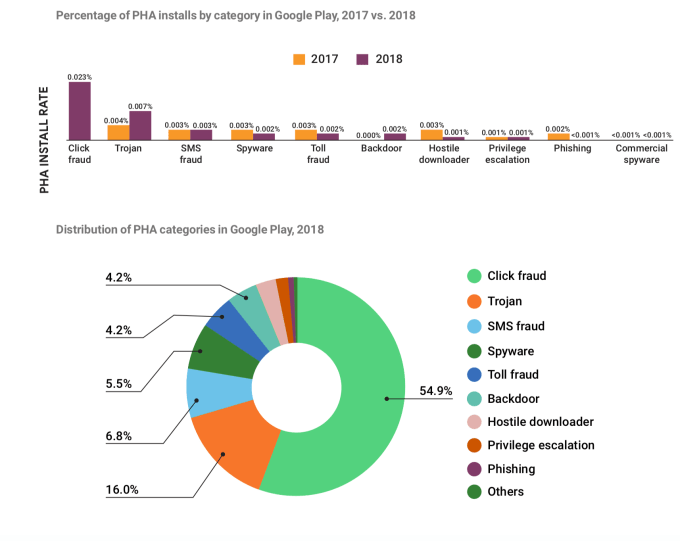

In terms of the categories that are covered by PHAs at the moment, click fraud is by far the highest category both in terms of install rates and distribution. Notably, 2018 was the first year that Google started tracking click fraud as a potentially harmful application: in the past it had been classified as a policy violation. This is one example of how it’s looking to cover more surfaces for potential vulnerabilities, but also a surprise to see that it wasn’t part of the mix before, considering how huge it is. Partly as a result of it now detecting and blocking click-fraud post recategroization, Google noted that it “expect[s] click fraud to remain a profitable fraud vector, but at a lower scale than in 2018.”

Google noted that the two biggest click fraud families were FlashingPuma and CardinalFall, and that the main target countries for click fraud attempts were the USA, Brazil and Mexico (USA and Brazil being two of Google’s biggest markets for Android).

While there are straight click fraud apps, Google notes that most are designed around other services, often something that a consumer might use daily — most commonly flashlights, music and gaming apps. In these, “an embedded SDK is executing click fraud in the background, often without the knowledge of the app developers themselves. Distributing click fraud code in this way is easily scalable and makes it easy for click fraud SDK developers to be present in the apps of hundreds or even thousands of developers,” Google notes in its report.

But even as Google gets more sophisticated and strict in how it handles third party players in its ecosystem, the problem continues to morph and find new areas to exploit.

Just last week, a report was published that highlighted how pre-installed apps — the non-Google apps that come on your device either fully installed or as a link to an install — were providing links into vast ecosystems of services that pull user data, and were difficult to remove for anyone but the most technically advanced.

Weeks before that, yet another tranche of 200 apps were identified that slipped in under the radar littered with adware (on top of another 85 apps also loaded with adware that millions of people downloaded months before). Adware isn’t the only ‘ware that has been found in Google apps: in November last year it was revealed that half a million people downloaded apps from Google Play containing malware, too.

And it was only two months ago that Google finally started to crack down and pull apps that were using legacy permissions to access users’ call logs and SMS messages. (Those permissions have been replaced by more privacy-focused APIs, but the fact is that that those permissions used to exist, and Google hadn’t stopped letting apps use them until quite recently.)

While much has been made of the open source nature of Android being one of the reasons that it’s misused in this way, another is the fact that a lot of apps are developed with open source components, and these can be ripe for exploitation. One recent report, in fact, found that no less that one in every five Android apps has vulnerabilities in it as a result of that open source usage.

While it’s misleading to think that Apple and iOS are not prey to similar kinds of exploits — they are — the fact that the Android ecosystem is simply so much bigger, and more open than the tightly controlled iOS platform, makes it an especially interesting target for malicious actors.

All these might not all be malicious in the sense of, for example, hacking financial information or disabling your device, but privacy of information and information security nonetheless go hand-in-hand. Having a grip on one leads to better control of the other.